Ann Stephen

Paul Klee DISTEL-BILD, 1924, 73

AN ALLEGORY OF LOVE & LEARNING

Summary

The essay proposes a new reading for Distel-bild [Thistle-painting, 1924], one of Paul Klee’s Sonderklasse (special class) of works that has long eluded interpretation. Painted at the beginning of Klee’s third year of teaching at the Bauhaus during a time of significant change, Distel-bild is no ordinary landscape or garden setting as the thistle, that is not a thistle, is a double-coded object. Adopting an allegorical mode, Klee casts the divisive debates of the early Bauhaus years in the language of a Hans Christian Anderson fairy tale. The essay argues that the painting both gently mocks and celebrates Johannes Itten’s role as a Bauhaus master and imagines how such ideas would spread. This new interpretation that aims to unlock the mystery of the painting’s organic and geometric forms, is informed by the broader reassessment of Klee as an intellectual engaged with contemporary ideas and avant-garde movements, rather than as a remote, naïve romantic.

Distel-bild [Thistle-painting, 1924, 73] in the National Gallery of Victoria, the only Paul Klee painting held in an Australian art museum, has eluded interpretation for almost a century.1 (FIG. 1) The Australian art historian Margaret Plant, who wrote a monograph on Klee, described it as “a mystery picture: the objects around the flower are indeterminate and involved in a drama known only to their world”.2 New research on the painting, particularly on its Bauhaus context, provides the key to unlocking the mystery of its organic and geometric forms. Such research is informed by the broader reassessment of Klee as an intellectual engaged with contemporary ideas and avant-garde movements, rather than as a remote, naïve romantic.

Distel-bild was painted in early 1924, at the beginning of Klee’s third year of teaching at the Bauhaus during a time of significant change. The following year, after the school moved from Weimar to Dessau, Klee’s teaching notes were published as Pädagogisches Skizzenbuch (Pedagogical Sketchbook) as the “Bauhausbücher 2”, in a Constructivist design by the newly-arrived master László Moholy-Nagy. The appointment of the Hungarian exile marked the decisive turn away from Expressionist mysticism and towards a more Constructivist orientation at the Bauhaus.

Interest has been sparked in Distel-bild because it bears Klee’s inscription, “S. – Cl”, the subject of considerable recent research.3 This acronym that stands for Sonderklasse (Special class) was used by the artist to identify those of his works he considered to be of the highest quality and were not to be sold. Klee scholar, Marie Kakinuma who wrote the entry on the Melbourne Klee in the catalogue of Sonderklasse works, distinguished it from his pre-Bauhaus Distel paintings, which identified the prickly plant as emblematic of Gothic architecture, “symbolising a thorny spiritual ascent”.4 For Distel-bild she suggests a fascinating Bauhausler reading, speculating that the subject might indeed concern the controversial expulsion of Johannes Itten. In 1919 Walter Gropius had appointed Itten amongst the first Bauhaus masters, to establish the Vorkurs (Preliminary Course), and he became a charismatic figure at the school. Amongst his regular exercises was one that involved drawing a thistle as an aid to sensitising students in material studies, as he explained:

“In front of me there is a thistle. My motor nerves feel a jagged, rapid movement. My senses, the sense of touch and face, grasp the sharp pointiness of its form, and my mind sees its nature […] It is obvious that I can draw a proper thistle only if the movement of my hand, my eyes and my mind correspond exactly to the intense pointed, pricking, painful form of a thistle: which means – character of movement equals character of form. This is the main statement of our whole research”.5

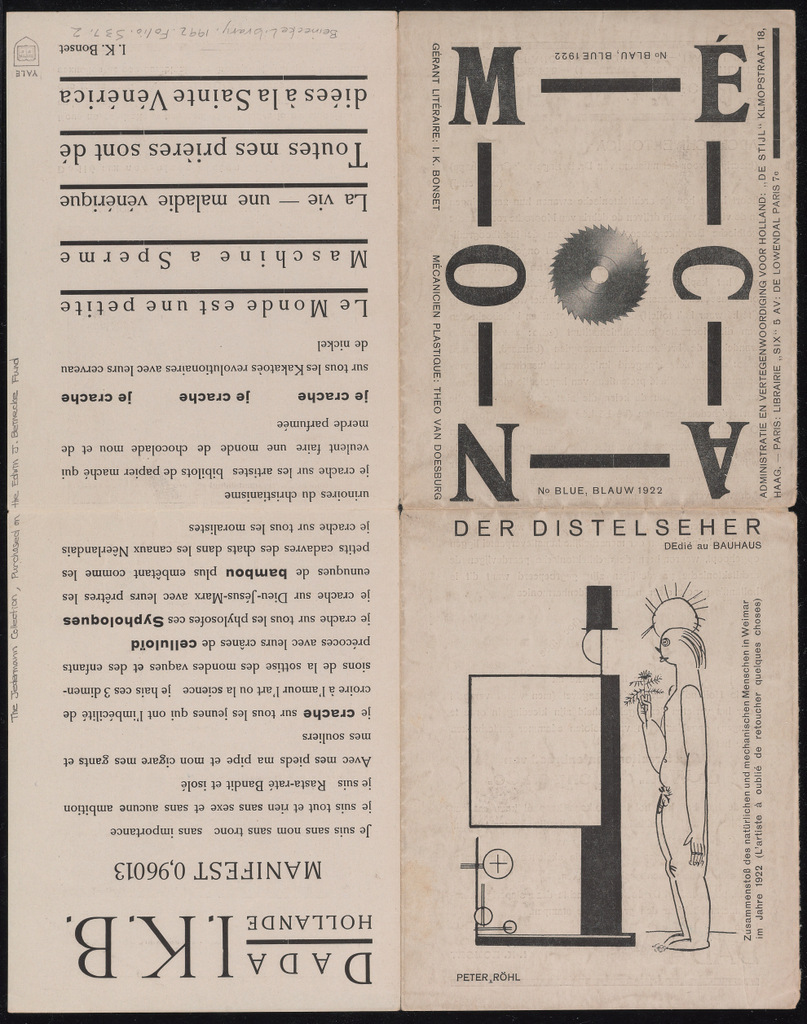

Itten’s teaching that combined sensory awareness with spiritualism would assume the proportions of a cult-like following among certain Bauhaus students. His messianic Mazdaznan ideology, an orientalist esoteric mysticism that swept through Germany in the early 1920s, was satirised by a cartoon published in the Bauhaus edition of Theo van Doesburg (under the pseudonym I.K. Bonset)’s Dadaist magazine Mécano showing a bleary-eyed nudist bearing a thistle confronting De Stijl’s “machine man”.6 (FIG. 2) By 1922 Itten was in open conflict with Gropius’s plans for the school that had been forced, by economic and political pressures, to become more market-orientated. Eva Forgács argues that Klee’s hiring had been part of Gropius’s policy to “moderate Itten’s influence”.7 As she recounts, “even Paul Klee, whose usual taciturnity and impartiality in public affairs earned him the nickname ‘The Good Lord’, was moved to comment trying to moderate the passions, from his own ethereal, cosmic viewpoint: ‘I welcome the fact that forces so differently orientated are working together in our Bauhaus. I also approve the conflict between these forces if its effect is evidenced in the final accomplishment. To meet an obstacle is a good test of strength for every force – provided it is an obstacle of an objective nature”. 8 Itten finally resigned in March 1923.

Kakinuma suggests that the geometric and constructive forms of triangles, cross-like bars and a circuit surrounding the plant in Distel-bild might allude to the new Constructivist tendencies in the Bauhaus program. Such a reading is consistent with Klee’s Seiltänzer, (Tightrope Walker) 1923, that has been interpreted as the artist’s own balancing act within an increasingly Constructivist-orientated Bauhaus.9 However, geometric forms were not only the domain of Constructivism. Klee was captivated by the abstract designs developed for Bauhaus festivals, films and theatre, like those dancing coloured shapes in Ludwig Hirschfeld Mack’s Farbenlicht-Spiel (Colour-light Plays) and Oscar Schlemmer’s Das Triadische Ballett (Triadic Ballet) with its new vocabulary of geometric forms. If the dark and delicate Distel-bild, made a year after Itten’s departure, is a veiled Bauhaus narrative, how do the elements in its abstract landscape contribute to this reading?

Klee’s 1923 essay “Wege des Naturstudiums” (Ways of Nature Study) advocated that a student’s “growth in the vision and contemplation of nature enables him to rise towards a metaphysical view of the world and to form free abstract structures which surpass schematic intention and achieve a new naturalness, the naturalness of the work”.10 Distel-bild’s metaphysical narrative appears to be enacted through a fairy tale about the life cycle of a thistle. The shallow, flattened space is theatrical, and as Plant has observed, “most of Klee’s figurative drawings and paintings and, indeed, many of his nature paintings, have a sense of the exposé upon the stage […] presented freize-like or frontally, often in a spotlight, as if on a stage”.11 At centre stage of Distel-bild is an oval that sprouts a geometric bloom, surrounded by spiky leaf-forms with a square of red dots or “seeds” at its heart.

In his lecture notes Klee famously described the process of reading a painting in terms of movement: “The eye must graze over the surface, grazing away and sharpening one part after the other […] The eye follows the paths established for it in the work”.12 The visual paths of Distel-bild suggest a movement akin to reading as the eye moves along the top of the painted cloth from left to right, observing the frayed, uneven edge of its exaggerated horizontal format while following a narrow path bordered by three linear forms, one straight and two curved. A subdued light leads down a diagonal striped path or paling fence that opens like a gate onto the centre of the painting where a teardrop-shaped mask hovers on a triangular base above a bell-shaped bloom that springs from the glowing oval thistle. Another visual path takes in the dark blue foreground marked on one side by a diagonal cross and on the other, by a small square framed in a crescent at the bottom right-hand corner. A year earlier in the watercolour Seelen Wanderung (Transmigration of a Soul 1923, 133), Klee had made a vertical play between a crescent moon and an earthbound cross; here in Distel-bild both are grounded. The fallen crescent might represent another mystically-inclined master, Lothar Schreyer, who left the Bauhaus several months after Itten, following the failure of his play Mondspiel (Moon play) in 1923.13

In Distel-bild all the forms are phantom-like, their faintly glowing silhouettes outlined against the thinly washed, cool blue-grey ground. Klee used a similar quasi-cubist effect of negative definition for several other works at this time, notably kleine Winterlandschaft mit dem Skiläufer, (small Winter landscape with a Skier, 1924, 85) and Ein Dorf als Reliefspiel (A village in playful relief, 1925, 140) though Distel-bild is a darker, more layered landscape. Through the transparent washes it is possible to see each gesture and painted stroke, from the faint blue dashes inside the top right curve to the dirty, reddish-brown blobs around the cross. In the centre, mid-ground where the action is concentrated there is a shift in temperature with warm pink and orange-tinged washes defining contours. Only the crimson red dots at the centre of the thistle are distinct, held in a rectangle surrounded by pale, orange light, and enclosed in an oval outlined in brown, purple and blue, itself surrounded by spiky forms. These jagged leaf-forms, raised like hands, appear as cartoon-like alerts signalling trouble, given emphasis by a series of five swiftly drawn, darker vertical strokes indicating a fall. The sense of downward movement is heightened by the tightly cropped forms along the top edge which suggests that Distel-bild’s extended rectangle originally formed the lower part of a larger painting.

For an artist fascinated by the literature of fairy tales, a crucial clue to unravelling this imaginary landscape lies in a story by Hans Christian Anderson, titled “What happened to the Thistle”.14 Like many of Klee’s paintings, Andersen’s thistle tale of love, longing and mortality has a garden setting, though mostly the story takes place beyond its cultivated borders. Here in the wilderness unruly animal and vegetative life abound:

Just outside the fence that separated the garden from a country lane, there grew a very large thistle. It was so unusually big with such vigorous, full-foliaged branches rising from the root that it well deserved to be called a thistle bush. No one paid any attention to her except one old donkey that pulled the dairymaid’s cart. He would stretch his old neck toward the thistle and say, “You’re a beauty. I’d like to eat you!”15 But his tether was not long enough to let him reach the thistle and eat her.

In the painting, a diagonal cross in the dark foreground is placed on one side of the thistle, marking it out as wasteland, while along the top edge runs a line of fence, a gate and two curved borders suggesting the outlines of cultivated garden-beds. The transformative event of Anderson’s tale takes place when the thistle captures the attention of one of the guests attending a garden party:

“The young people amused themselves on the lawn, where they played croquet. As they strolled about in the garden, each young lady plucked a flower and put it in a young man’s buttonhole. The young lady from Scotland looked all around her for a flower. But none of them suited her until she happened to look over the fence and saw the big, flourishing thistle bush, full of deep purple, healthy-looking flowers. When she saw them she smiled, and asked the young heir of the household to pick her one of them for her”. 16

The plucking of the bloom not only seals the romance, but fuels the aspirations of the outsider, beyond the pale, who reflects on her changing fortunes.

“I must be more important than I thought, she said to herself. I really belong inside, not outside the fence. One gets misplaced in the world, but I now have one of my offspring not only over the fence but actually in a button hole!”17

The idea of being outside the pale is keenly felt through the narrative, as is the temporality of life. Seasons pass, love blossoms and the couple are married, yet nothing changes for the increasingly marginalised thistle bush until the newly-weds revisit her: The young couple, who now were man and wife, came down the garden walk along the fence. The bride looked over the fence, and said, “Why, there still stands the big thistle, but it hasn’t any flower left”.

“Yes, there’s the ghost of one – the very last one”. Her husband pointed to the silvery shell of the flower- a flower itself.

“Isn’t it lovely! she said. We must have one just like that carved around the frame of our picture”.18

Life, however, remains the same for the thistle-bush beyond the garden, and she is led to consider her fate, in the bad-lands of the wilderness as winter approaches: “What strange things can happen to one, said the thistle. My oldest child was put in a buttonhole, and my youngest in a picture frame. I wonder where I shall go”.19

The old donkey by the roadside looked long and lovingly at the thistle. “Come to me, my sweetie, he said. I cannot come to you because my tether is not long enough”.20

But the thistle did not answer.

Klee’s painting appears to summon up the epiphany at the end of the fairy-tale. His muted tones resist any dramatic point of colour or tonal contrast in favour of a subdued and wintery northern twilight. In that light, the last silvery shell of the thistle sprouts like a ghostly bell. A sunbeam, in the form of a pink, glowing tear-drop mask, appears like an apparition, its triangular beam echoing the thistle’s last bloom. Light, the source of life throughout the year, now responds to the musings of the old mother thistle who is finally resigned to her fate as winter approaches:

“When one’s children are safe inside, a mother may be content to stand outside the fence”.

“That’s a most honourable thought, said the sunbeam. You too shall have a good place”.

“In a flowerpot or in a frame?” the thistle asked.

“In a fairy tale,” said the sunbeam. And here it is.21

In Anderson’s tale, the outsider is redeemed from oblivion through art, drawing attention back to the act of storytelling. Even though no fairy-tale book by Hans Christian Andersen can be found in Paul Klee's library, dispersed after his sacking from Dusseldorf as a “degenerate artist” in 1934, Andersen’s stories were an integral part of any German middle-class childhood. Indeed in the mid-19th century, as the literary historian Cay Dollop explains, “in both Denmark and Germany the fairy tale was born because tales from the other country were translated. In each country they called the attention of readers (clearly, grownups in need of reading material for children) to this new genre”.22 The art historian Annie Bourneuf, in her recent study on the artist, has described how Klee’s instincts are redemptive, as he seeks out abandoned archaic forms and “takes up negative terms from writing about art with which he was familiar – the hieroglyph, the schema, the fairy tale – as positive models allowing him to conceptualize hybrids of writing and picturing”.23 Klee's interest in fairy tales was intimately associated with the childhood of his son Felix for whom he made some 50 dolls and puppets between 1916 and 1924. It was also at this time that Klee included Distel-bild in an exhibition he held with the Austrian artist, Alfred Kubin, who had illustrated a collection of fairy tales by Hans Christian Andersen published by Bruno Cassirer in 1922.24

Klee’s small painting adopts the scale of this minor literature of childhood, however any explicit reference to Andersen’s tale or Itten’s fate is well concealed, as it is no illustration but enacts the moment of revelation in abstract terms. The allegory, inscribed in a plant’s cycle of life and death, reveals how the outcast has the possibility of attaining immortality in art, like Klee’s own act of retrieving the offcut with its frayed, uneven edges and transforming it through the act of painting. In fusing the fairy tale with that of the Mazdaznan’s fate, the artist reimagines the expulsion from the “garden“ of the Bauhaus in order to redeem the outsider for posterity, in some kind of cosmic reconciliation of conflict.

The painting’s “special class” confirms the importance of the Melbourne Klee for the artist. Indeed, Klee expert Charles W. Haxthausen has identified another relatively small but significant group in his oeuvre, including any painting bearing the title bild (picture), as it “becomes an image of an image […] a kind of meta-picture […] they are parodies of traditional pictorial genres or visual artefacts”.25 Parody, as Haxthausen explains, was the central focus of Clement Greenberg’s 1950 essay on Klee. Greenberg observed that the artist’s irony was “never bitter […] when he has rendered it harmless by negation, he takes it fondly back”.26 Distel-bild is no ordinary landscape or garden setting as the thistle, that is not a thistle, is a double-coded object. The painting both mocks and celebrates the sharp pointiness of Itten’s role in the Bauhaus and imagines how such ideas would spread.

The recent identification of the painting’s significance for Klee makes its reclusive subject all the more intriguing. Kakinuma notes it was exhibited three times in Germany, the year it was painted and then was sent to Galerie Vavin-Raspail as one of “39 aquarelles de Paul Klee”, part of his first solo exhibition in Paris in October 1925. In 1949 the Klee Society, founded after the death of the artist’s widow, released works from the “special class” and it was sold from the Klee estate by Galerie Rosengart in Lucerne to a Chicago collector, Charlotte Picher Purcell, who several years later consigned the work to a London dealer where it was acquired by the National Gallery of Victoria. Such a peripatetic existence ensured a long exile for the Distel-bild before its narrative could be seen.

Notes

- Distel-bild, 1924, gouache and watercolour on linen, laid down on thin card with traces of ruled ink and pencil, 21 x 40.6 cm (image) 38.1 x 54.3 cm (card), Paul Klee Stiftung, Catalogue Raisonné No. 3441, National Gallery of Victoria (NGV). The painting was exhibited in 1925 at the Paris-based Galerie Vavin-Raspail of Max Berger. See Baumgartner u. a, pp. 8–39. In 1953 the painting was purchased by the Trustees of the NGV from Reide and Lefevre Ltd, London.

- See Plant 1968, p 127.

- See Kersten/Okuda/Kakinuma 2015. The catalogue combines a relatively small group of less than 300 works of the Sonderklasse (Special class), a ranking Klee used between the years 1925 and 1933 for his production between 1901 and 1933, in an oeuvre of nearly nine thousand works.

- See Kersten/Okuda/Kakinuma/Frey 2015, p. 128. The four pre-Bauhaus thistle paintings are Distelgarten (Thistle Garden) 1918, Arkansas Arts Center, Distelblüte (Thistle Bloom) 1918, location unknown, Stillleben mit d. Distelblüte (Still Life with Thistle Bloom) 1919, location unknown, and Das Haus zur Distelblüte (The Thistle Flower House) 1919, Städel Museum, Frankfurt am Main.

- See Itten 1978, p. 220. Also see student work from Itten’s course, Joost Schmidt, Thistles, 1920, charcoal drawing, in Wingler 1978, pp. 281, 283.

- The cartoon by Bauhaus student Karl-Peter Röhl appeared in the Bauhaus edition of Mécano, No. Blue, 1922. See also Christoph Wagner u. a., Das Bauhaus und die Esoterik: Johannes Itten, Wassily Kandinsky, Paul Klee, Leipzig: Kerber, 2005.

- See Forgács 1995, pp. 71–2.

- See Forgács 1995, pp. 63–64.

- This convincing interpretation by Cathrin Klinsöhr-Leroy is made through close reference to Klee’s own lectures. See Klinsöhr-Leroy 2016, pp. 126–130.

- See Klee 1923, p. 17.

- See Plant 1978, p.10.

- See Klee 1925, p. 33.

- See Weber 2009, p. 78.

- See Andersen 1869. Hans Christian Anderson, »Hvad tidselen oplevede« (»What happened to the Thistle«) 1869, translated by Jean Hersolt, H.C. Anderson Centre website, (andersen.sdu.dk/vaerk/register/index_e.html) cited 20/04/2017.

- Dollerup concludes his study of the two-way translation between the tales of the German Grimm brothers and the Danish Hans Christian Anderson, writing: »The emergence of the literary fairy-tale genre is an early (perhaps even the earliest) situation in which translations create, influence, and promote national literary output, for the simple reason that the genre was considered primarily as literature for children, who would be unfamiliar with foreign languages.« See Dollerup 1995, pp. 101, 102.

- See Bourneuf 2016, p.10.

- Andersen/Kubin 1922. I am grateful to Walther J. Fuchs for his many helpful suggestions including drawing my attention to the exhibition “Zwei Zwei Künstlerphantasten. Paul Klee und Alfred Kubin, Kunsthalle Mannheim, 23.11.1924-10.1.1925.

- See Haxthausen 2016, pp. 159–160.

- Haxthausen 2016 quoting Greenberg, p. 160.

Bibliography

Andersen 1869

Hans Christian Andersen, »Hvad tidselen oplevede« (What happened to the Thistle) 1869, translated by Jean Hersolt, H.C. Anderson Centre website, (andersen.sdu.dk/vaerk/register/index_e.html), cited 20 April 2017.

Andersen/Kubin 1922

Hans Christian Andersen and Alfred Kubin, Die Nachtigall ; Die kleine Seejungfrau ; Der Reisekamerad, Berlin: Cassirer, 1922, Vol. 11.

Baumgartner u.a.

Michael Baumgartner u. a, »Paul Klee und die Surrealisten. ‚In Weimar blüht eine Pflanze, die einem Hexenzahn gleicht’. (Louis Aragon)«, in Paul Klee und die Surrealisten, Ostfildern: Hatje Cantz-Verlag, 2016.

Bourneuf 2016

Annie Bourneuf, Paul Klee The Visible and the Legible, Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2016.

Dollerup 1995

Cay Dollerup, »Translation as a Creative Force in literature: the birth of the European Bourgeois Fairy Tale«, The Modern Language Review, Vol. 90, No. 1, Jan. 1995, pp. 94-102..

Forgács 1995

Ēva Forgács, The Bauhaus idea and Bauhaus politics, Budapest: Central European University Press, 1995.

Haxthausen 2016

Charles W. Haxthausen, »Klee’s Parodic Genres«, Paul Klee. Irony at work, ed. Angela Lampe, Prestel: Centre Pompidou, 2016, pp. 159-165.

Itten 1978

Johannes Itten, »Analysen alter Meister«, 1921, in Johannes Itten. Werke und Schriften, ed. Rotzler, Zurich: Orell Füssli, 2. ergänzte Aufl., 1978.

Kersten/Okuda/Kakinuma/Frey 2015

Wolfgang Kersten, Osamu Okuda and Marie Kakinuma, Stefan Frey (Mitwirkende), Paul Klee: Sonderklasse. Unverkäuflich (Special class Unsaleable), ed. Zentrum Paul Klee, Bern, Museum der bildenden Künste Leipzig, 2015.

Klee 1923

Paul Klee, »Wege des Naturstudiums« (Ways of Nature Study), Staatlisches Bauhaus Weimar, 1919–1923, Munich 1923, reprinted in Paul Klee Creative Confession and other writings, London: Tate Publishing, 2013, pp. 15-17.

Klee 1925

Paul Klee, »Pädagogisches Skizzenbuch« (Pedagogical Sketchbook), Bauhausbücher 2, Munich 1925, reprinted London, Faber and Faber Limited, 1968.

Klinsöhr-Leroy 2016

Cathrin Klinsöhr-Leroy, »In Equilibrium. Paul Klee at the Bauhaus«, Paul Klee. Irony at work, ed. Angela Lampe, Centre Pompidou, Prestel, 2016, pp. 126-130.

Plant 1968

Margaret Plant, »The Modern European Collection«, in National Gallery of Victoria: Painting Drawing Sculpture, ed. Ursula Hoff, F.W. Melbourne: Cheshire Publishing Pty Ltd, 1968.

Plant 1978

Margaret Plant, Paul Klee Figures and Faces, London: Thames & Hudson, 1978.

Weber 2009

Klaus Weber, »Lothar Schreyer, Death House for a woman, c. 1920«, Bauhaus 1919–1933: Workshops for Modernity, eds Barry Bergdoll, Leah Dickerman, New York: Museum of Modern Art, 2009.

Wingler 1978

Hans Wingler, The Bauhaus. Weimar Dessau Berlin Chicago, Cambridge, Massachusetts and London, England: The MIT Press, 1978.

![Fig. 1 Paul Klee, Distel-bild , 1924, 73 [Thistle-painting] , gouache on canvas on paper on cardboard, 18/16,5 cm x 40,6 cm, ©National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne, Inv.Nr. 2999-4.](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/547344abe4b03e7d0378a6bd/1507731345327-TNC67E9IXMF3U4G4TQ4P/1_Distel-bild_1924_73.jpg)